CanHOPE is a non-profit cancer counselling and support service provided by Parkway Cancer Centre, Singapore.

UNDERSTANDING CANCER: DEFINITION, CAUSES AND PREVENTION

What is Cancer?

When the genetic material (DNA) of a cell becomes damaged or altered, it produces mutations that affect normal cell growth and division. When this happens, cells do not die when they should, and new cells form when the body does not need them. These extra cells may form a mass of tissue called a tumour. When these tumours become malignant, they become cancerous and can spread to other parts of the body.

Cancer by the Numbers: What You Need to Know

Cancer is a leading cause of death in Singapore, responsible for nearly 25% of all fatalities each year (Ministry of Health Singapore, 2023).

According to GLOBOCAN 2022 data (extracted December 2024), Singapore recorded the highest age-standardized incidence rates (ASIR) in Southeast Asia: 235.9 per 100,000 for men and 231.0 per 100,000 for women after adjusting for differences in population age structures to allow fair comparisons across countries. In other words, an ASIR tells you how many new cancer cases per 100 000 people would occur each year if the population had a fixed age distribution.

Based on National Cancer Centre Singapore (2024) findings, the top three cancers among men were prostate, colorectal and lung cancer, while among women they were breast, colorectal and lung cancer:

Prostate Cancer (Men): The most commonly diagnosed cancer among men in Singapore, accounting for 17.4% of all male cancer cases, according to the Singapore Cancer Registry Annual Report 2022. This reflects a significant public health concern and highlights the growing burden of this disease within the male population. The risk of developing prostate cancer increases markedly with age, with the majority of cases occurring in men over the age of 60. This local trend mirrors global patterns, where the median age at diagnosis is approximately 66 years (Singapore Cancer Registry Annual Report 2022; NCBI, 2023; PMC, 2019).

Breast Cancer (Women): Accounting for 29.6% of female cancers, breast cancer incidence has risen steadily, partly due to demographic shifts and improved screening uptake (National Registry of Diseases Office, 2022).

Lung Cancer: Remains one of the most common and deadly cancers both globally and in Southeast Asia, including Singapore. According to the Singapore Cancer Registry Annual Report 2022, lung cancer accounts for a significant proportion of cancer diagnoses and continues to be associated with high mortality, largely because many cases are detected only at advanced stages.

The World Health Organization also highlights that lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide, while regional data show that it remains among the top five cancers in Southeast Asia, contributing substantially to cancer-related deaths (WHO, 2023; The Lancet Regional Health – Southeast Asia, 2024; Singapore Cancer Registry Annual Report 2022).

Colorectal Cancer: The third most common cancer in both men and women worldwide, representing 13.3% of cases in Singapore. This cancer continues to pose a significant health burden, with an observed increase in incidence among younger adults under 50 (Singapore Cancer Registry, 2022).

Most Common Cancers

Among the many cancer types, three stand out for their high incidence and impact. Understanding why these cancers are so widespread and how they develop can inform both prevention and early detection strategies.

Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal cancer often begins as benign polyps in the colon or rectum. Over years, genetic and environmental factors—such as diets high in red and processed meats and low physical activity—can drive these polyps to become malignant (National Registry of Diseases Office, 2021). For an average-risk person, faecal occult blood testing (FOBT) is recommended annually while a colonoscopy is advised every 10 years, starting at age 50. Early polyp removal can prevent progression to invasive cancer.

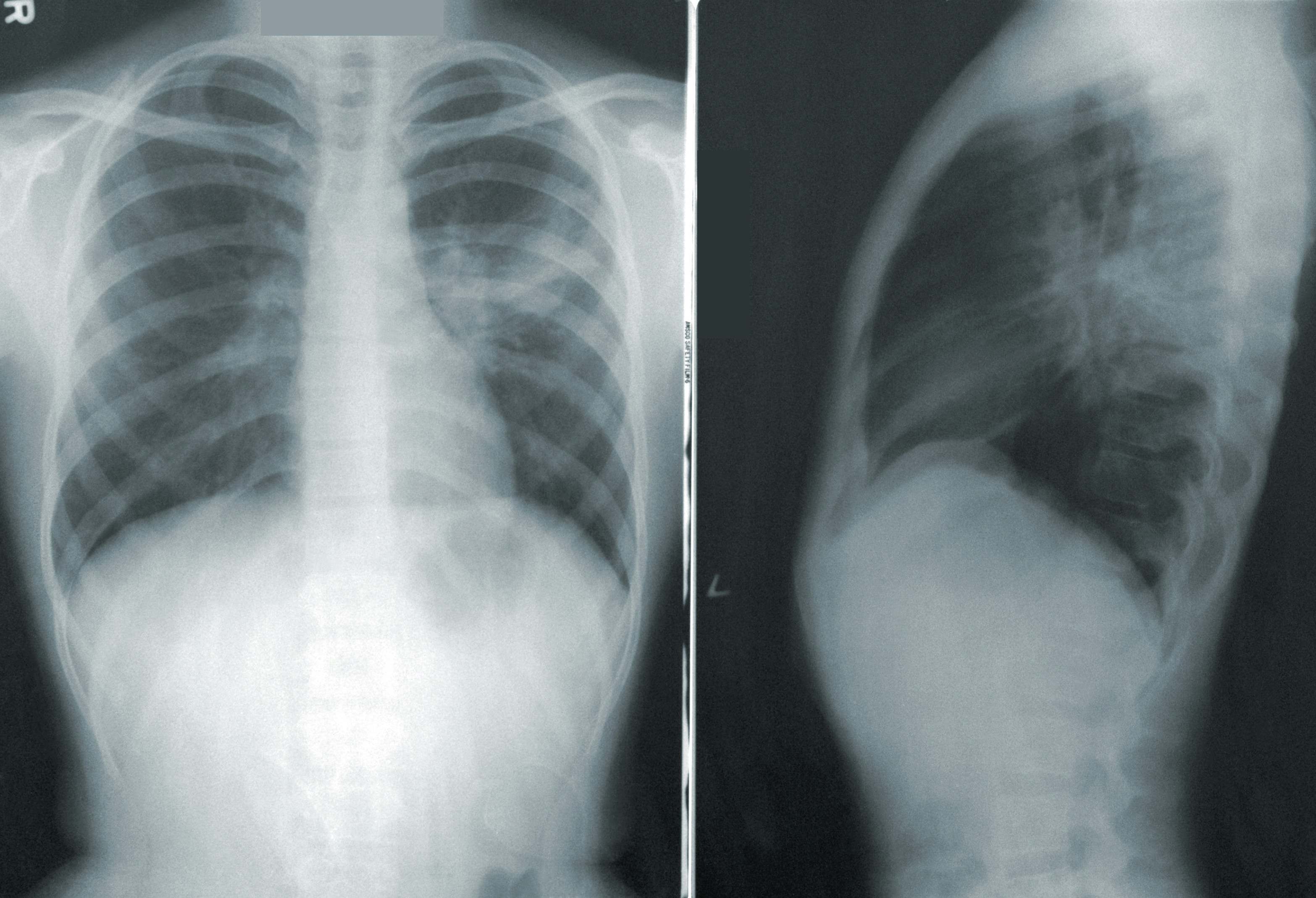

Lung Cancer

Lung cancer arises when epithelial cells in the airways accumulate damage from tobacco smoke, air pollutants or workplace toxins. Non-small cell lung cancer accounts for approximately 85% of cases, with small-cell lung cancer comprising most of the remainder . Symptoms like chronic cough or breathlessness often appear late, and in Singapore nearly half of non–small cell lung cancers (NSCLC) occur in never-smokers . Low-dose CT screening is currently recommended only for individuals aged 55–74 with a heavy smoking history (30 pack-years or more, smoking within the past 15 years); patients with a strong family history of lung cancer should also discuss screening options with a licensed healthcare professional.

Breast Cancer

Breast cancer originates in milk ducts or lobules and is influenced by hormonal, genetic and lifestyle factors. It is recommended for an average-risk individual to do a monthly self-examination from the age of 30 and regular mammogram screening from the age of 40 for early breast cancer detection.

A common early finding is ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), a non-invasive stage detected by mammography as microcalcifications. Invasive ductal carcinoma can present as a hard lump, skin dimpling or nipple discharge, and advances in imaging and treatment have significantly improved survival rates when detected promptly (National Registry of Diseases Office, 2021).

Why These Cancers Are Common

Colorectal, lung, breast cancers are Singapore’s most commonly diagnosed malignancies, driven chiefly by ageing-related DNA damage, genetic and hormonal factors, and lifestyle behaviours such as diets high in red and processed meats, physical inactivity, alcohol consumption and tobacco smoking.

National screening initiatives annual faecal immunochemical testing for individuals aged 50–75 (Ministry of Health Singapore, 2012) and free biennial mammograms for women aged 50–69 (Ministry of Health Singapore, 2010) boost early detection. Public health efforts that promote risk reduction and timely intervention seek to lower incidence and improve survival.

How Cancer Begins: Causes You Should Know

Cancer results from interactions between inherited genetic predispositions and environmental exposures. >br/>Carcinogens, such as ultraviolet light, ionising radiation, tobacco smoke, certain chemicals, and oncogenic viruses—damage DNA.

When repair mechanisms fail, these mutations accumulate, setting the stage for malignant transformation.

Everyday Habits That Raise Your Cancer Risk

Cancers develop when various risk factors induce genetic and cellular changes. Key risk factor categories include:

Modifiable Risk Factors

- Tobacco use

- Excessive alcohol consumption

- Unhealthy diet (high in red and processed meats, low in fruits and vegetables)

- Obesity

- Physical inactivity

Environmental and Occupational Exposures

- Ultraviolet radiation (sunlight, tanning beds)

- Ionising radiation (medical imaging, radon gas)

- Chemical carcinogens (asbestos, benzene, aflatoxins)

- Air pollution and particulate matter

Infectious Agents

- Human papillomavirus (HPV), linked to cervical and oropharyngeal cancers

- Hepatitis B and C viruses (HBV, HCV), associated with liver cancer

- Helicobacter pylori infection, a risk factor for gastric cancer

Age and Genetics

- Advancing age leads to accumulation of DNA mutations over time

- Inherited genetic mutations (e.g., BRCA1/2, TP53) predispose to specific cancers

Understanding and modifying these factors can significantly reduce individual cancer risk. Explore risk reduction strategies on our Prevention & Screening page.

Is Cancer Genetic?

While most cancers aren’t inherited and usually result from random DNA changes that occur over a person’s life, some families carry specific gene faults that can raise the odds of developing certain cancers.

Germline mutations in genes like BRCA1, BRCA2, TP53 and others can predispose individuals to breast, ovarian, colorectal and other tumour types.

Genetic counselling and testing enable at-risk individuals to consider targeted screening and risk-reducing strategies.

Types of Cancer

Cancers are classified by the tissue or cell of origin. Below are the primary categories, each encompassing multiple subtypes with distinct characteristics and treatment considerations.

Carcinomas

Carcinomas arise from epithelial cells that line organs and skin. They represent about 80–90% of all cancers and include lung, breast, prostate, colorectal and skin (both melanoma and non‑melanoma) cancers. Their behaviour and prognosis vary widely by organ site and molecular profile.

Sarcomas

Sarcomas develop from connective tissues—bone, cartilage, fat, muscle and blood vessels. Though rare (<1% of adult cancers), they are more common in children and young adults. Key subtypes include osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma and liposarcoma.

Hematologic Cancers

This group includes leukaemias (cancers of blood-forming tissues) and lymphomas (cancers of the lymphatic system). Common leukaemias include acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) and chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML), while lymphomas encompass Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin subtypes. These cancers often require systemic therapies; learn more on our Blood & Lymphatic Cancers section.

Other Types

Several less common cancers fall outside the above categories. Neuroendocrine tumours originate from hormone-producing cells, germ cell tumours from reproductive cells, and central nervous system tumours from brain or spinal cord tissue. Rare entities such as mesothelioma and ocular melanoma also belong here.

How Cancer Develops

The carcinogenic process unfolds in stages: initiation (DNA mutation), promotion (clonal proliferation), progression (malignant transformation) and metastasis (secondary growths). Tumour microenvironment factors—angiogenesis (the process of forming new blood vessels. Tumours trigger it by releasing signals like VEGF, so they get the oxygen and nutrients needed to grow and spread), immune evasion, stromal interactions—also play critical roles.

Signs and Symptoms

While each cancer presents uniquely, persistent signs such as unexplained weight loss, chronic fatigue, fever, night sweats, lumps, bleeding or organ-specific changes (e.g., chronic cough, dysphagia) should not be ignored. Early recognition improves outcomes. To review symptom checklists by cancer type, consult our Signs & Symptoms guide.

Diagnosis and Staging

Diagnosis begins with a patient history and physical exam to gather symptoms and risk factors. Blood tests look for abnormal values or tumour markers. Imaging scans (CT, MRI, PET) provide detailed internal pictures to locate masses. Biopsy, where a small tissue sample is examined under a microscope, to determine if one has cancer.

Once confirmed, staging uses the TNM system:

- T (Tumour): Size and extent of the main tumour (T0–T4).

- N (Node): Whether nearby lymph nodes have cancer cells (N0–N3).

- M (Metastasis): Whether cancer has spread to other body parts (M0 or M1).

Combining these categories assigns a stage (I–IV). Early stages (I–II) often mean localised disease with higher cure rates; later stages (III–IV) indicate spread requiring more complex treatment.

Treatment Options

Cancer treatment is multifaceted, tailored to disease type, stage and individual health. Below are the primary modalities:

Surgery

Surgical removal of tumours remains a cornerstone for many solid cancers. Techniques range from minimally invasive laparoscopic procedures to complex resections, aiming to excise malignant tissue while preserving organ function. Outcomes depend on tumour location, stage and surgical expertise.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy uses high-energy radiation beams to destroy cancer cells. External beam radiation and brachytherapy deliver precise doses to tumours, minimising harm to surrounding healthy tissue. It is often combined with surgery or chemotherapy to shrink tumours pre-surgery or eradicate residual disease.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy involves cytotoxic drugs that target rapidly dividing cells. Regimens may be curative or palliative and are administered systemically or regionally. Side effects such as nausea, hair loss and immunosuppression are managed with supportive measures. For more information on chemotherapy protocols, side-effect management and patient support, visit Chemotherapy overview.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy harnesses the body’s immune system to fight cancer, using checkpoint inhibitors, monoclonal antibodies and adoptive cell therapies (e.g., CAR-T). These treatments can produce durable responses, particularly in melanoma, lung and haematologic cancers. For detailed information on treatment options, eligibility criteria and side effect management, explore the immunotherapy page.

Targeted Therapy

Targeted therapies block specific molecular pathways critical for cancer cell survival and proliferation, using small molecules or antibodies against mutated proteins like EGFR, HER2 and BRAF. Selected based on genetic profiling, these treatments often have fewer systemic side effects. See our Targeted Therapy resources.

Hormone Therapy

Hormone therapies suppress or block hormones that fuel the growth of certain cancers, including breast and prostate cancers. Common agents include tamoxifen, aromatase inhibitors and luteinising hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) analogues.

Palliative and Supportive Care

Palliative care focuses on symptom relief and quality of life, addressing pain, nausea, fatigue and emotional well-being. It integrates with curative treatments and extends through survivorship and end-of-life care. For comprehensive support services, see Palliative Care.

Screening & Early Detection

Screening programmes—such as mammography for breast cancer, Pap smears for cervical cancer, colonoscopy for colorectal cancer and low-dose CT scans for lung cancer—detect early-stage disease when treatment is most effective.

Guided by Ministry of Health (MOH)’s Screen for Life, screening is recommended for the following individuals:

- Breast Cancer: Mammogram every year (40–49 years), 2 years (50 years and above).

- Cervical Cancer: Pap smear every 3 years (25–29); HPV test every 5 years (30–69).

- Colorectal Cancer: Colonoscopy every 5 to 10 years (50 years and above).

Prevention

Effective cancer prevention employs a multi-pronged approach, targeting modifiable behaviours and environmental exposures. Key strategies include:

Lifestyle Modifications

Lifestyle modifications benefit everyone and are especially important for people living with cancer. Eating a balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables and whole grains; cutting back on red and processed meats; moderating alcohol; and getting at least 150 minutes of moderate activity each week can help prevent cancer and support recovery. Caregivers can encourage these habits by cooking nutritious meals together and planning gentle exercises. For practical tips, learn more on our Nutrition and Exercise pages.

Vaccinations

Vaccines can prevent cancers linked to infectious agents. The HPV vaccine protects against cervical, anal and oropharyngeal cancers, while the HBV vaccine lowers liver cancer risk.

Environmental & Workplace Safety

Reducing exposure to known carcinogens in the environment and workplace—such as asbestos, benzene and radon—lowers cancer incidence. Implementing policies and protective measures, like proper ventilation and personal protective equipment, is critical.

Regular Screening & Early Detection

While technically a secondary prevention strategy, screening facilitates the early identification and removal of precancerous lesions. Programmes include mammography, Pap smears and colonoscopy.

Research and Future Directions

Advances in Cancer Genomics: By sequencing a tumour’s DNA to identify mutations such as BRCA or EGFR, clinicians can pinpoint genetic “weak spots” and select targeted therapies that home in on those specific alterations.

Liquid Biopsies: Circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) assays detect tiny fragments of cancer DNA in a simple blood sample, giving doctors an early, real‐time view of how your cancer is changing so they can adjust treatment before scans reveal progression.

AI-Driven Diagnostics and Prognostics: Machine learning models sift through medical images and health records to flag subtle lesions and forecast a cancer’s likely course, acting as a second set of expert eyes to help guide diagnosis and treatment planning.

Next-Generation Immunotherapies: CAR-T cell therapy and personalised neoantigen vaccines retrain your own immune cells to recognise tumour-specific proteins, turning your body’s defences into a precision weapon against cancer.

Clinical Trials: Phase I–III studies methodically test new drugs and treatment combinations for safety, dosing and effectiveness compared to today’s standards, offering patients access to cutting-edge options under careful medical oversight.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are 5 interesting facts about cancer?

Based on the Singapore Cancer Registry Annual Report 2022 Infographic:

- Cancer is common: Cancer is one of the leading causes of death in Singapore.

- Prevalence: More than 82,000 new cancer cases were diagnosed in Singapore from 2018 to 2022.

- Survival rates are improving: The 5-year age-standardised survival rate is about 56.6% for males and 63.7% for females in Singapore.

- Common types: The most common cancers in males are colorectal, lung, and prostate cancer. For females, they are breast, colorectal, and lung cancer.

- Rising trends: The number of new cancer cases in Singapore has increased over the years, likely due to an ageing population and improved detection.

2. How can cancer start?

A single cell can become cancerous when mutations activate oncogenes or disable tumour suppressor genes. Additional genetic and epigenetic changes then drive uncontrolled growth, formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis) and the ability to invade nearby tissues and spread (metastasis) in a process known as carcinogenesis.

3. How long can a cancer patient live?

Survival depends on the type of cancer, the stage at diagnosis, and access to treatment.

4. Do all cancer patients suffer severe cancer pain?

No, not all cancer patients experience severe pain. Cancer pain can vary greatly from person to person. Some may have no pain at all, while others might have mild, moderate, or severe pain. With the right treatment and support, most cancer pain can be managed effectively. It is important for patients to let their doctors know about any pain they experience so that it can be properly treated.

5. Can cancer be cured?

The chance of curing cancer depends on a few important factors, such as the type of cancer, its specific features, and how much it has spread when it is found. Generally, cancer is more likely to be cured if it is detected and treated early, before it has spread. In these early stages, surgery to remove the tumour, sometimes along with chemotherapy or radiotherapy can often lead to a cure.

For cancers that have already spread to other parts of the body (advanced cancer), a complete cure is less likely. However, new and exciting treatments are being developed all the time. These advances can help people with advanced cancer live longer and enjoy a better quality of life.

- Ministry of Health Singapore. (2021). Disease burden. Retrieved May 13, 2025, from https://www.moh.gov.sg/others/resources-and-statistics/disease-burden

- National Cancer Centre Singapore. (n.d.). Cancer statistics. Retrieved May 13, 2025, from https://www.nccs.com.sg/patient-care/cancer-types/cancer-statistics

- Health365. (2023). Cancer is the #1 cause of death in Singapore. Retrieved May 13, 2025, from https://www.health365.sg/cancer/

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. (2022). Singapore fact sheet: GLOBOCAN 2022 [PDF]. Global Cancer Observatory. Retrieved May 13, 2025, from https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/702-singapore-fact-sheet.pdf

- National Registry of Diseases Office. (2022). Singapore Cancer Registry Annual Report 2022 [PDF]. National Registry of Diseases Office. Retrieved May 13, 2025, from https://www.nrdo.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider3/default-document-library/scr-ar-2022_web-report6c6e8522-cf39-416f-9390-5fe903065927.pdf?sfvrsn=3712e8bb_1

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. (2022). Singapore fact sheet: GLOBOCAN 2022 [PDF]. Global Cancer Observatory. Retrieved June 24,, 2025, from https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/702-singapore-fact-sheet.pdf

- Ministry of Health Singapore. (2012). CRC screening [Web page]. Retrieved May 15, 2025, from https://www.moh.gov.sg/newsroom/crc-screening

- Ministry of Health Singapore. (2010). Extending Medisave for screening mammograms and colonoscopies [Web page]. Retrieved May 15, 2025, from https://www.moh.gov.sg/newsroom/extending-medisave-for-screening-mammograms-and-colonoscopies Breast Cancer

- HealthHub Singapore. (2024). Breast cancer: Symptoms, causes, and prevention [Web page]. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://www.healthhub.sg/a-z/diseases-and-conditions/breastcance

- National Cancer Institute. (2025, April). Breast cancer prevention (PDQ®) summary [Web page]. Retrieved May 15, 2025, from https://www.cancer.gov/types/breast/hp/breast-prevention-pdq

- National Registry of Diseases Office. (2022). Singapore cancer registry annual report 2022 [PDF]. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://www.nrdo.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider3/default-document-library/scr-ar-2022_web-report6c6e8522-cf39-416f-9390-5fe903065927.pdf?sfvrsn=3712e8bb_1 Cancer Mechanisms & Types

- Cleveland Clinic. (2023). Carcinoma: Types, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment [Web page]. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/23180-carcinoma

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. (2008). Carcinomas overview. In NCBI Bookshelf. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9963/

- Parkway Cancer Centre. (2024). What causes cancer? [Web page]. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://www.parkwaycancercentre.com/sg/learn-about-cancer/about-cancer/what-causes-cancer

- Raffles Medical Group. (2024). What you need to know about sarcoma cancer [Web page]. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://www.rafflesmedicalgroup.com/health-resources/health-articles/what-you-need-to-know-about-sarcoma-cancer/ Colorectal Cancer

- HealthHub Singapore. (2024). Colorectal cancer screening at a glance [Web page]. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://www.healthhub.sg/live-healthy/screening_colorectal_cancer_nuhs

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. (2018). Colorectal cancer. In NCBI Bookshelf. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470380/

- National Neuroscience Institute. (2023). More younger adults diagnosed with early-onset colorectal cancer in Singapore [Web page]. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://www.nni.com.sg/news/patient-care/more-younger-adults-diagnosed-with-early-onset-colorectal-cancer-in-singapore

- National Cancer Institute. (2025, April). Colorectal cancer prevention (PDQ®) summary [Web page]. Retrieved June 24, 2025, from https://www.cancer.gov/types/colorectal/hp/colorectal-prevention-pdq

- National Registry of Diseases Office. (2022). Singapore cancer registry annual report 2022 [PDF]. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://www.nrdo.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider3/default-document-library/scr-ar-2022_web-report6c6e8522-cf39-416f-9390-5fe903065927.pdf?sfvrsn=3712e8bb_1 General Statistics, Survival & FAQ

- National Registry of Diseases Office. (2022). Singapore cancer registry annual report 2022 infographic [PDF]. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://www.nrdo.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider3/default-document-library/scr-ar-2022_infographicb76e7873-3cbf-4620-9499-881195f22917.pdf?sfvrsn=f4375122_1

- Parkway Cancer Centre. (2024). 5 common questions about cancer pain answered [Web page]. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://www.parkwaycancercentre.com/sg/treatments#FAQ Lung Cancer

- Parkway Cancer Centre. (n.d.). Why lung cancer is rising among non-smokers. Retrieved June 24, 2025, from https://www.parkwaycancercentre.com/sg/news-events/news-articles/news-articles-details/why-lung-cancer-is-rising-among-non-smokers

- SingHealth. (n.d.). Lung cancer – causes, symptoms & treatments. Retrieved June 24, 2025, from https://www.singhealth.com.sg/patient-care/conditions-treatments/lung-cancer

- National Cancer Institute Singapore. (2024). Lung cancer: Cancer information [Web page]. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://www.ncis.com.sg/cancer-information/cancer-types/lung-cancer

- National Cancer Institute. (2025, April). Lung cancer prevention (PDQ®) summary [Web page]. Retrieved May 15, 2025, from https://www.cancer.gov/types/lung/hp/lung-prevention-pdq

- Singapore Cancer Registry Annual Report. (2022). Singapore cancer registry annual report 2022 [PDF]. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://www.nrdo.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider3/default-document-library/scr-ar-2022_web-report6c6e8522-cf39-416f-9390-5fe903065927.pdf?sfvrsn=3712e8bb_1

- The Lancet Regional Health – Southeast Asia. (2024). Lung cancer in Southeast Asia: Trends and burden. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lansea/article/PIIS2772-3682(24)00080-5/fulltext#:~:text=Equity-,Introduction,%25%20of%20the%20cancer%20deaths).&text=1.&text=In%20Southeast%20Asia%2C%20although%20lung,causing%20166%2C260%20(10.9%25)%20deaths.&text=2.&text=Most%20registries%20from%20Southeast%20Asian,five%20leading%20types%20of%20cancer.&text=3.&text=4.&text=In%20India%2C%20lung%20cancer%20accounts,and%2066%2C279%20deaths%20(7.8%25).

- World Health Organization. (2023). Lung cancer: Key facts [Web page]. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lung-cancer Principal Causes & Incidence

- Ministry of Health Singapore. (2023). Principal causes of death [Web page]. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://www.moh.gov.sg/others/resources-and-statistics/principal-causes-of-death

- The Lancet Oncology. (2025). Cancer incidence and mortality in Southeast Asia: Analysis of 2022 data. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanonc/article/PIIS1470-2045(25)00017-8/abstract?rss=yes Prostate Cancer

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. (2019). Prostate cancer. In NCBI Bookshelf. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470550/

- National Registry of Diseases Office. (2022). Singapore cancer registry annual report 2022 [PDF]. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://www.nrdo.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider3/default-document-library/scr-ar-2022_web-report6c6e8522-cf39-416f-9390-5fe903065927.pdf?sfvrsn=3712e8bb_1

- PubMed Central. (2019). Prostate cancer incidence and age at diagnosis [Article]. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6497009/ Screening Guidelines

- HealthHub Singapore. (2024). Colorectal cancer screening at a glance [Web page]. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://www.healthhub.sg/live-healthy/screening_colorectal_cancer_nuhs Skin Cancer (Non-Melanoma)

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. (2023). Nonmelanoma skin cancer. In NCBI Bookshelf. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441949/

- National Health Service. (2024). Non-melanoma skin cancer: What is non-melanoma skin cancer? [Web page]. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/non-melanoma-skin-cancer/what-is-non-melanoma-skin-cancer/

- PubMed Central. (2016). Nonmelanoma skin cancer epidemiology [Article]. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4954336/ Stomach Cancer

- Mayo Clinic. (2024). H. pylori infection – Symptoms and causes [Web page]. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/h-pylori/symptoms-causes/syc-20356171

- MDPI. (2024). Aging, cancer, and Helicobacter pylori [Article]. Retrieved May 28, 2025, from https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/25/23/12826